Do you remember the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin? It is an old fairy tale about a musician who was hired to rid the town of rats by charming them with his flute playing. But, when the townsfolk refused to pay him as they had promised, he exacted his revenge by leading all the town’s children away as well. Is Taylor Swift a modern-day Pied Piper? I suggest we take a closer look at Swifties: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swifties

Outside of this group, it seems that most Americans don’t have the appetite for and interest in seriously paying attention to anything. We seem to be a sea of mindless and braindead citizens following whatever grabs our limited attention? The movie Idiocracy is on point. Our culture is so riddled with soundbites and frenetic messaging scientists now claim our attention span has dropped from about 2-3 minutes 50 years ago to something less than 8 seconds. Watch how short modern commercials are compared to when you were young.

I personally believe the lengthy exposure of screen time with its toxic soup of videogames, social media, and AI generated personalized content addicts us and capturing our eyeballs and is a part of why today’s children and young adults have higher incidents of ADHD and other difficulties. I grew up without TV since it hadn’t been invented yet. I had a radio and could read books. Of course attention spans then were longer and necessary. Against this backdrop, I suggest you look carefully at the behaviors of Taylor Swift concert goers. The following extended video summary of her recent tour is chilling:

https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/music/2024/12/05/taylor-swift-eras-tour-reporter-personal-journey/76711565007/

If you watched even a small part of the video segment, and you are a conservative older person you probably will say it reminds you of the Beetles Tour or Elvis Presley. Yes, in some ways that’s true, but the size of the crowds and the range of audience demographics should be a wake-up call to anyone in modern marketing. Plus, the way Taylor Swift creates community experiences is a Harvard Case Study in modern social interactions.

If you just watched the referenced video and shrugged your shoulders in disgust, you are vulnerable to those who know what has happened and why. If you can’t figure it out, hire the ones that have … or you are toast in this new world. Curiosity may have killed the cat, but it is your key to success in how others are redefining brand identity, awareness, and loyalty. Her fans are fanatics. She has not merely upped the game … she has reinvented it.

Here is an article summarizing how fans felt about her 3.5 hour concert: https://wapo.st/4fi6dRq The formula she used to connect with such a wide-ranging audience not only delivered the experience of a lifetime, but it also moves these same individuals to be in an ongoing relationship to her.

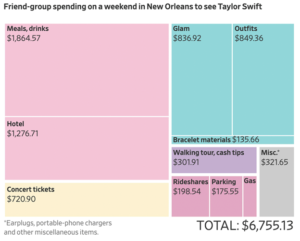

Look at the financial impact of this. It is not just about her ticket sales that have redefined the online ticket selling business because of its intensity. Look at the impact on the local economy in the chart below summarizes. She generates about ten times more than the prices of her tickets … which are also incredibly high … bordering on the absurd:

If you are hungry for more economic impacts, take a look at this article in the WSJ: https://www.wsj.com/economy/taylor-swift-fan-economic-impact-eras-tour-revenue-a9c00005?st=E1Wonm&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

It is so easy to just dismiss this young lady or to chalk this up to an otherwise bored modern youth element. No … there is something profound going on here. Her fans know the words of her songs and sing along during the 3+ hour concert. Their antics actually create seismic impacts! When I started my engineering career we studied the Tacoma Narrows Bridge failure. Could a new rating for safety now include a Taylor Swift Concert rating?

So, if you don’t know what’s been happening and why … you may soon be “paying the Piper!”